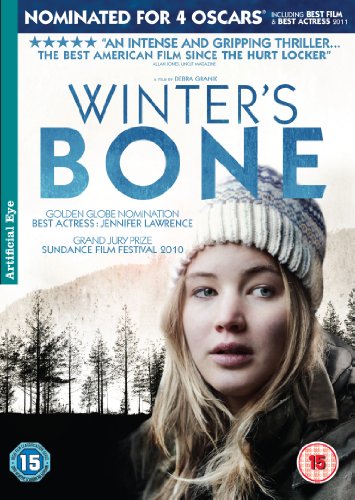

Dir. Debra Granik

Starring: Jennifer Lawrence, John

Hawkes, Lauren Sweetser, Garret Dillahunt

There are unwritten codes that

govern life in the Ozarks of southern Missouri. Blood and kinship is important.

One should never ask for help; it should be offered. Never step foot inside a

man’s house without the man (and it is always the man) granting permission. And

keep your mouth shut – don’t gossip, don’t blacken someone’s name, and never,

ever, talk to the police.

It is this web of codes that

17-year-old Ree Dolly (Jennifer Lawrence) must navigate. She is responsible for

looking after two younger siblings and a mother suffering from mental illness

in the absence of her crank-cooking father Jessup. When he skips bail – having

left all the family’s property as security – she has to find him and persuade

him to return for trial to stop their home being seized. Once that trial date

has passed, however, her mission changes; the only way to protect her family is

to present proof that her father is dead.

It soon becomes apparent that

these are missions which are not popular. No one wants Ree to be asking the

questions she is asking. It becomes clear that there is a conspiracy of

silence. Those that do know the truth about her father’s disappearance are

prepared to fight to keep their secrets; even those that do not know the truth

recognise that asking questions is a sure-fire way to get into trouble. Her

uncle Teardrop (John Hawkes) puts it plainly: if she discovers who killed his

brother he does not want to know. Knowing puts him in peril. As the film ends

he states that he knows the name of the killer. He says it quite sadly. There

are two ways to read his reaction. Firstly, that he knows that he is now in

danger because of his knowledge (which would explain why he returned to banjo

to Ree). Or secondly, that he is now expected to avenge his brother’s death,

perpetuating a bloodfeud. He is not keen for either result. When Ree pokes her

nose in too far the fact that she is an innocent 17-year-old girl can only

protect her so far. She is beaten – but only by women because the local code of

honour prevents men from laying hands upon her. She is asked what she thinks

should happen next. She bites back that maybe they should kill her. Melissa

comments that ”That idea’s been said

already”. Ree only wants to get to the truth to protect her family. She is

so devoted to this that she is kinda hard-core. To get to the end of the story

she has to be exposed to an awful side of life that most people are thankfully

sheltered from. Her determination is inspiring.

It is a hardscrabble existence in

the hills. The homes are hand-made, people have guns to hunt for the table, and

wood needs chopping for the fire. And Ree and her family are the poorest of the

poor, even though they are not yet quite at the bottom. Skinning a shot

squirrel her younger brother asks whether they eat the intestines. Ree’s answer

is “Not yet” implying that she knows

there will come a time when they will have to just to survive. Before his

arrest her father was engaged in crime – principally the production and sale of

methamphetamines (“crank”). Ree

accepts this as fact, even seems proud that he was good at it. She may not take

drugs herself, but she appreciates that it was a career that provided for the

table. The wooded and difficult terrain makes the Ozarks the perfect place to

secrete meth labs. It is a location that encourages clannishness; the

inhabitants all seem to be related to each other, even if at several removes.

|

| Teardrop refused to accept another three points on his licence |

It is not a pleasant film to

watch. There is no glamour, just a stubborn heroism. The nearest it comes to

sudden action is the suspenseful scene where Teardrop faces down the sheriff

(Garret Dillahunt). That is one scene that will definitely live long in the

memory, along with the passage where Ree is finally taken by boat to bring back

her father. There is a creeping dread pervading the entire picture, as the

viewer realises that there is very little hope for people from these

communities. Shipping out with the army is about the best that they can hope

for. It is very affecting and very memorable. And in Jennifer Lawrence’s Ree

Dolly it has provided us with an inspiring heroine for these troubled times.

What have I learnt about

Missouri?

The Ozark hills look quite bleak,

and the life of its inhabitants seems even bleaker. This seems a land where the

only escapes are childbirth or joining the army. Or drugs. Home-made

laboratories for ‘crank’ (methamphetamines) dot the landscape. Everyone seems

to be either making it or using it, and the local criminal bosses are not

people to be messed with. Those who threaten their control get beaten or

killed. Bodies are buried or fed to the hogs. Even for those who do get

involved with this illegal subculture life is hard. People live in rundown

farms or cluttered trailers. Guns are common and so is hunting – squirrel and

deer helps to round out the diet. Any vehicle that is not a truck is remarked

upon as being out of place. The men wear beards and baseball caps and the women

seem beaten down by life. There is no social services safety net except for the

kindness and generosity of neighbours.

Legitimate business seems to

revolve around cattle. Fiddle and banjo bluegrass music is the soundtrack to

celebrations. Ties of kinship are important – but they cannot get one

everything. Talking about things that out not to be mentioned is a bad idea.

Can we go there?

I’m not sure I’d particularly

want to travel down into the Ozarks. The forested hills are meant to be areas

of great beauty. The stark winter landscapes shown in this film suggest

barrenness rather than beauty to my eyes. And the local craft industry isn’t

much to my taste either.

But for die-hard fans, the film

was shot entirely on location in Christian and Taney counties in southern

Missouri, stretching down to the Arkansas Line. Forsyth Public School

featured, as did the stock yards

in Springfield.

Overall Rating: 4/5

No comments:

Post a Comment