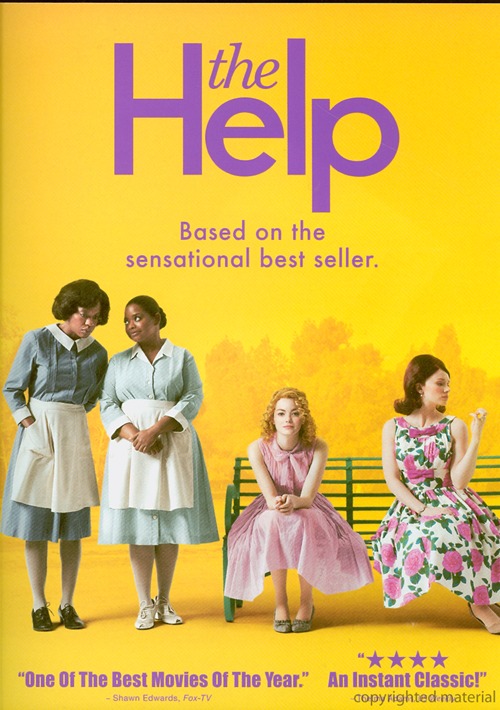

Dir. Tate Taylor

Starring: Emma Stone, Viola

Davis, Octavia Spencer, Bryce Dallas Howard

In The Help reference is made to the character of Mammy in Gone With the Wind, and that no one ever

asked her opinion. Well this is what The

Help is. It is a film looking at the racial segregation that still existed

in the South nearly a century later from the viewpoint of black house-servants.

Except that those servants are

not writing their own story. Wrongs are righted, but only because a crusading

white woman persuades them to tell her their stories. Much like To Kill a Mockingbird or Fried Green Tomatoes… black characters

can only get some measure of justice or respect because of an enlightened white

character. Here that character is Eugenia ‘Skeeter’ Phelan (Emma Stone), back

from university and itching to become a journalist. Her big idea is to

interview some of the maids around town to see how they feel about being

treated the way they are. This in itself is refreshing. Aibileen (Viola Davis)

says “No one had ever asked me what it

feel like to be me. Once I told the truth about that, I felt free.” Skeeter

has very modern attitudes for early-‘60s Jackson. She sympathises with blacks

(she becomes the first white to ever set foot inside Aibileen’s house), she

wants a career, she is quite unfussed about finding a husband, and can even

laugh when her mother suggests she might be suffering from “unnatural urges” (i.e. lesbianism) and need “a cure”. So hurrah for her.

But she does not endanger herself

by wanting to write this book. She merely faces ostracism. Any of the black

servants participating in this risk being fired, arrested, or worse. Minny

(Octavia Spencer) is blacklisted once she is fired. Yule May (Aunjanue Ellis)

is beaten and arrested for theft. Aibileen had a son whose workplace death went

unremarked, and the real-life killing of local black leader Medgar Evers

provides a backdrop to some of the action. Nor do the contributors get much

benefit. All they get is Skeeter’s advance shared between them; Aibileen

herself is fired. Meanwhile Skeeter herself heads off for a new career as a

writer in New York. There is a scene where Aibileen and Minny tell her to go

because she has burnt all her bridges in Jackson, but one cannot help but

compare the way she leaves the film, buoyed up by the servants’ gratefulness

and her mother’s pride, with the solitary walk back to an empty house that

faces the unemployed Aibileen. “In just

ten minutes the only life I knew was done.” Skeeter’s life begins with her

book. Aibileen’s ends.

As one might notice, I have some

issues with the central premise of the story. Is it historically the case that

blacks had to be ‘saved’ by enlightened whites, or is it just that the original

novel by Kathryn Stockett and this film were designed to appeal to white

audiences? I felt that the movie started slowly and confusingly – although it

certainly picked up pace in the second half – and that the various subplots

around Skeeter’s love-life could have been successfully excluded. I found

Skeeter quite un-engaging; it is only Emma Stone’s wilful gawkiness (such as

her clumpy walk and frizzy hair) that saves her from being an annoying paragon.

What saves the film is some great

characterisation. Viola Davis is good value for her Academy Award nomination as

the steady, nurturing, principled Aibileen, and Octavia Spencer is even better

value as the sassy Minny (“Minny don’t

burn fried chicken”). Some great character actresses are wasted in their

roles – I’m looking particularly at Coal

Miner’s Daughter’s Sissy Spacek as Hilly’s mother, and Allison Janney (of Hairspray and Juno) as Skeeter’s mother.

Jessica Chastain provides heart and comic relief as the ditzy Celia Foote, a

Marilyn-like blonde similarly ostracised from Jackson’s social circles because

of the perception that she is “white

trash”. Stealing the show, though, is Bryce Dallas Howard. Her Hilly

Holbrook has to be one of the most unpleasant film characters of recent times.

She is the queen of the mean cheerleaders - a snobbish, spiteful, patronising

racist. As a leading light of the White Citizens’ Council she is the driving

force behind forcing the help to use outside toilets (her concern being

motivated by the fact that “they carry different

diseases than we do”, and would thereby put their children at risk by using

the same lavatory). She can be seen watching when Yule May is arrested and

beaten by the police. Thankfully she gets her comeuppance, which leaves a very

bitter taste in her mouth.

|

| Minny's Mississippi Mud Pie: the secret ingredient isn't love |

There was a bit of a media frenzy

when The Help was released, and it hoovered

up lots of Oscar nominations. I may be out on a very lonely limb here, but I can’t

help but think that this was largely due to the concept behind the film rather

than the merits of the film itself. It’s human and humane and it looks at a

time of great inhumanity in America – it’s precisely the sort of thing the

Academy love. I am reminded of the exchange between Ricky Gervais and Kate

Winslett in Extras that she wanted to

do a Holocaust movie because she was desperate to finally win an Oscar… and the

fact that she did finally win an Oscar for her role in The Reader, which was about the Holocaust. The film is fine… it’s

just not great. I have heard some very positive comments about the source

novel, however, so maybe I will enjoy that more if I read it.

What have I learnt about

Mississippi?

What struck me about this

depiction of Mississippi in the early 1960s was that white people did not so

much look down on blacks as a lesser race, but more that they looked at them as

a lesser species. Hilly Holbrook’s insistence that black servants use separate

toilets to prevent them passing on diseases to white children is one example;

another is the casual way in which Aibileen’s son was dumped outside a

blacks-only hospital following his accident. And this is not just the view of

isolated individuals. White Citizens Councils were widespread and the actual

laws of the state not just authorise segregation, they mandated it. Even to

speak against racial segregation was a crime. One cannot help but feel that the

State of Mississippi felt very scared of its black population.

And yet there was a clear

reluctance of that population to stick their neck above the parapet. They had

been successfully cowed by legal and illegal oppression. In the film Medgar

Evers is shown speaking out against the situation; he is then shot dead. The church is shown giving the population hope, but counselling against action.

There was a clear class divide in

Jackson. If one was black, the best one could hope for was a low-paid job as a

servant, cook, or construction worker. One would live in a completely different

area of town (literally across the tracks). No matter how well one saved,

sending ones children to college would be economically impossible.

It was interesting to see that

the Mississippi state flag incorporated the Confederate ‘stars and bars’ – i.e.

it incorporated the flag of an institution that fought to preserve slavery. And

one might say that not much has changed – one servant talked of being left to

her owner’s daughter in her will.

There were good white employers.

White children obviously did develop attachments to their black nursemaids. One

story about a doctor buying a patch of land just so his maid could take a

short-cut to walk was particularly touching. And Celia and Johnny Foote are

genuinely hospitable towards Minny, treating her as a friend. In fact, early in

their relationship it is quite clear that Minny is made uncomfortable by

Celia’s refusal to respect traditional master-servant boundaries.

Can we go there?

The Help is firmly set in Jackson, Mississippi. And while the film

was shot on location in Mississippi, only a few genuine places in Jackson made

it to the screen – the New Capitol Building, where Skeeter goes to find the

laws on segregation, the Mayflower Cafe, where Skeeter and Stuart have their date, and Brent’s Drugs.

On the whole the screen ‘Jackson’

was actually Greenwood,

about 100 miles further north. The wonderful folks at the Visitors Bureau there

have helpfully put together a map

identifying which locations were used. So, for instance, the Whittington

Farm was used for the exteriors of the Phelan farm and a residence on River

Road for the interior, the Hollbrooks lived on Grand Boulevard and the Leefolts

on Poplar Steet. The bus stop was at Little Red Park, and the church used was

the Little Zion Church on County Road 518. The scenes at the Jackson Journal were filmed in what were

the offices of the Clarksdale Press

Register in Clarksdale until 2010.

Overall Rating: 3/5

No comments:

Post a Comment